It’s 9:30 on a Monday morning at an NHS trust. Your team has just merged a pull request updating firewall rules for the new Databricks workspace. Ten minutes later, the pipeline fails — not because Azure Firewall itself is broken, but because someone accidentally typed 10.0.0.0/35 instead of /24 in the CSV file. Now the deployment’s stuck, the data engineering team can’t access their workspace, and you’re explaining to stakeholders why a single CIDR typo has halted a critical data platform deployment.

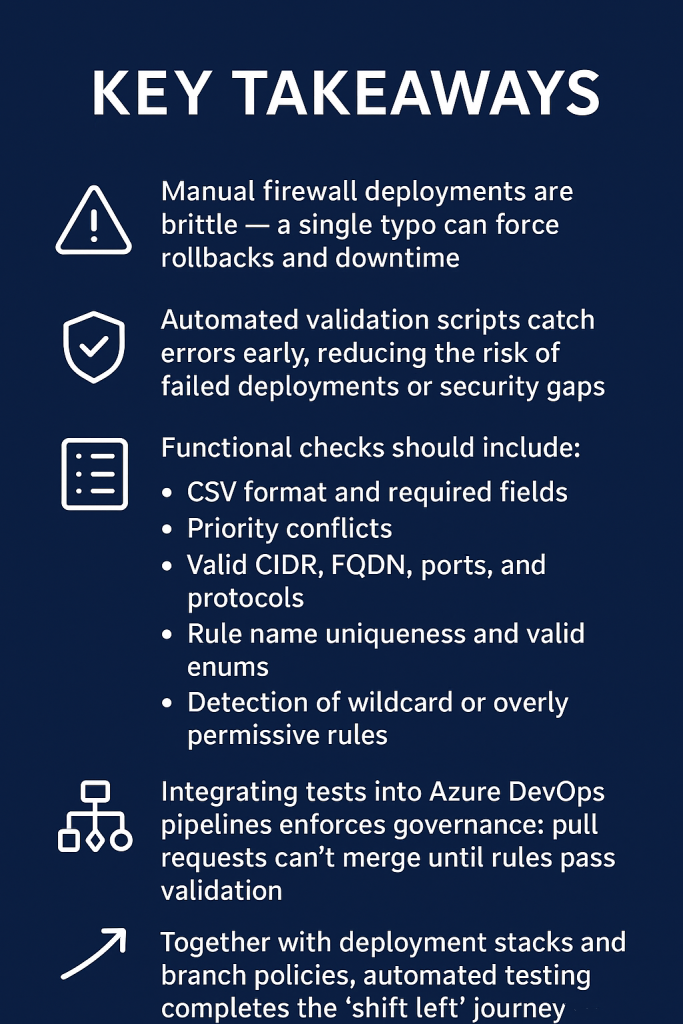

Automated tests are the difference between hoping your firewall rules work and knowing they do. By validating rules before they ever reach deployment, the pipeline becomes a safety net — catching mistakes early and ensuring changes are both secure and reliable. This is the third and final post in my series on Azure Firewall rules as code.

So this is the third and final part of the series. In the first post, I took the original code and adapted it to meet the customer’s requirements, adding a conceptual hub network so we could use it as a test bed. The second post showed how I integrated this into Azure DevOps, deploying with Azure Deployment Stacks and introducing approvals on pull requests to bring governance into the workflow.

This final post now focuses on implementing automated tests. The goal is simple: reduce the chance of introducing a security gap or incorrectly formatting the CSV file that sits at the heart of the process. By validating the rules before they ever reach deployment, the pipeline becomes a safety net, catching mistakes early and ensuring changes are both secure and reliable.

The Problem with Manual Deployments

If you’ve ever implemented Azure Firewall rules by code, you’ll know how unforgiving it can be. The slightest mistake can leave the firewall deployment in a failed state. The firewall itself remains functional, but you’re forced to revert your changes, amend the deployment, and try again.

I’ve been caught by this multiple times, including while building this solution. One example was deploying a rule with an incorrect IP group. The deployment got stuck, and even after correcting the file, the error persisted. The only way forward was to roll back to the previous rule and then re‑implement it with the correct group.

The IP group error I mentioned is just one example. I’ve also encountered rules with reversed port ranges (500-100 instead of 100-500) that failed silently. Another time, a rule with Block instead of Deny sat in the CSV for days because Azure Firewall only accepts specific enum values, and there was no validation catching it before deployment.

Why Automated Tests Matter

With errors like these, I wanted to reduce the chance of introducing mistakes as much as possible. While the specific IP group error isn’t yet covered in my script (something I’ll look to add), I built up Test-FirewallRulesCsv.ps1 to run a number of automated checks against the CSV file that drives the whole process.

These tests validate formatting, schema, and logical consistency before deployment, acting as a safety net to catch issues early.

Functional Requirements for the Test Script

With that in mind, I set out a list of functional requirements that I wanted the test script to deliver. Each requirement was chosen to reduce the risk of failed deployments or security gaps, and to make sure the CSV file driving the firewall rules was always valid.

CSV format and required columns Ensures the file structure is correct and all mandatory fields are present. Without this, the pipeline could break before even parsing the rules.

Priority conflicts within rule collection groups Detects overlapping priorities that can cause unpredictable behaviour. Clear, unique priorities are essential for consistent rule enforcement.

Valid CIDR notation for IP addresses Confirms that IPs are correctly formatted. A malformed address can block legitimate traffic or leave gaps in protection.

function Test-CidrNotation {

param([string]$Cidr)

if ($Cidr -notmatch '^(\d{1,3}\.){3}\d{1,3}/\d{1,2}$') {

return $false

}

$ip, $prefix = $Cidr -split '/'

# Validate each octet is 0-255

# Validate prefix is 0-32

...

}This function validates CIDR notation in two passes. First, it checks the basic format using regex. Then it validates that each IP octet is between 0-255 and the prefix is between 0-32 for IPv4. This catches errors like 256.168.1.1 or /35 that would cause deployment failures.

Valid FQDN formats Checks that domain names are syntactically correct. This prevents rules from silently failing when they reference invalid hostnames.

Valid port numbers and protocols Ensures only supported values are used. Incorrect ports or protocols can make rules ineffective or cause deployment errors.

Rule name uniqueness within collections Prevents duplicate names, which can lead to confusion and misapplied rules. Unique identifiers are key for maintainability.

Valid enum values for rule types and actions Confirms that rule definitions use only expected values (e.g., Allow or Deny). This avoids misconfigurations that could weaken security.

Wildcard destination rules Flags overly permissive rules (like *) that pose a security risk. These are easy to slip in during testing but dangerous in production.

This list sets the foundation for the script. Each check is designed to fail fast in the pipeline, surfacing issues before they reach deployment. That way, engineers can fix problems early and avoid the painful rollback cycles I described earlier.

Lets give it a test

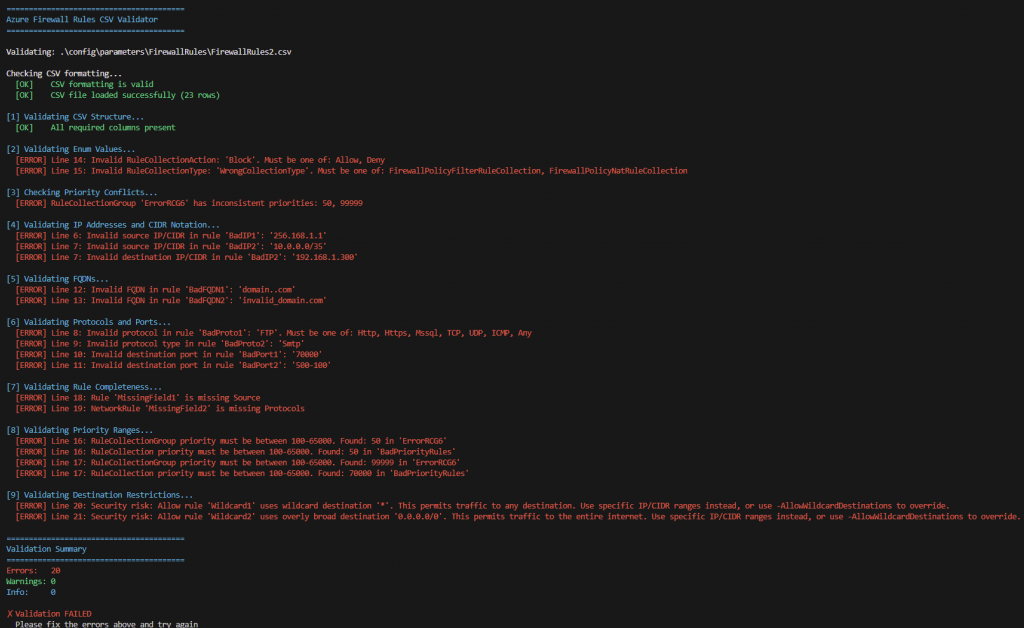

To demonstrate the script’s effectiveness, I deliberately created a CSV with various common errors — some I’d encountered in production, others I wanted to guard against. The goal was to validate that the script catches the mistakes before they reach Azure.

I’ve created some valid and some invalid rules in the file on purpose, so I’ll run the script and see how well my validation script picks up on the errors:

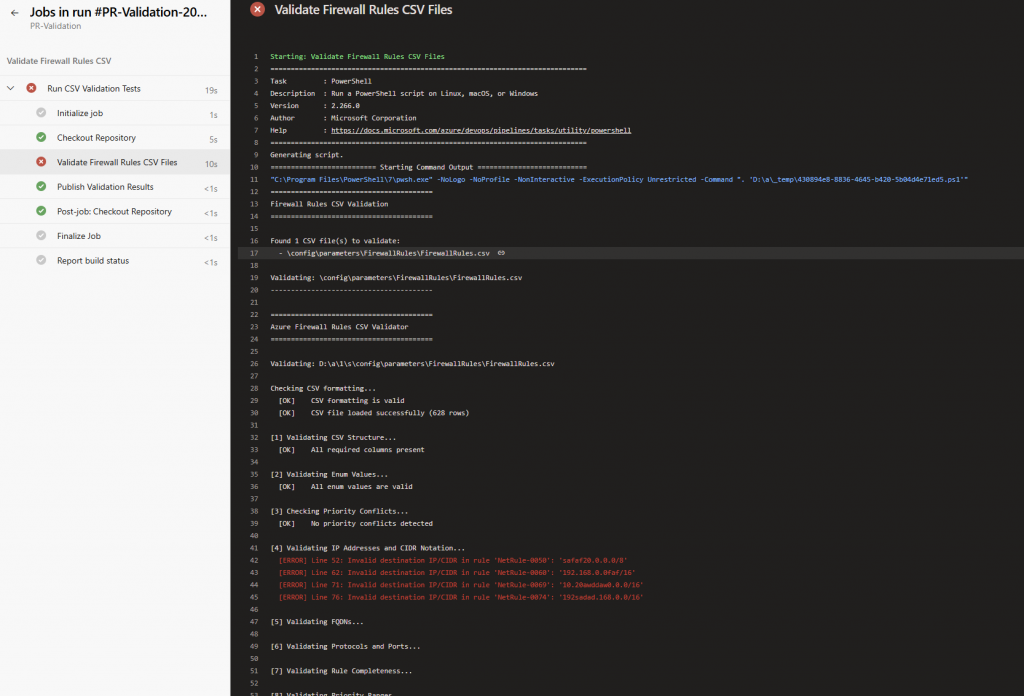

As you can see from the above image, a number of failures have been detected, either due to formatting, incorrect values or wildcard/any issues

So I’ll address the issues with some following changes. These demo errors are illustrative and not security-critical.

IP Address Errors:

| Issue | Before | After | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invalid octet | 256.168.1.1 | 192.168.1.1 | Max octet is 255 |

| Invalid CIDR prefix | 10.0.0.0/35 | 10.0.0.0/24 | Max CIDR is /32 |

| Invalid octet | 192.168.1.300 | 192.168.1.100 | Max octet is 255 |

Protocol Errors:

| Issue | Before | After | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unsupported protocol | FTP | TCP | FTP not valid |

| Invalid for ApplicationRule | Smtp:25 | Https:443 | Smtp not valid for ApplicationRule |

Port Errors:

| Issue | Before | After | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Out-of-range port | 70000 | 8080 | Valid range: 1–65535 |

| Reversed range | 500-100 | 100-500 | Start must be < end |

FQDN Errors:

| Issue | Before | After | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Double dots | domain..com | domain.example.com | Invalid syntax |

| Underscore in domain | invalid_domain.com | valid-domain.com | Use hyphens |

Enum/Type Errors:

| Issue | Before | After | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invalid action | Block | Allow | Must be Allow or Deny |

| Invalid collection type | WrongCollectionType | FirewallPolicyFilterRuleCollection | Must match expected enum |

Priority Errors:

| Issue | Before | After | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Out-of-range priority | 50 | 600 | Valid range: 100–65000 |

| Out-of-range priority | 99999 | 600 | Valid range: 100–65000 |

| Duplicate priority | 1000 | 1001 | Must be unique |

Missing Fields:

| Issue | Before | After | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empty source | (empty) | 10.7.0.0/24 | Required field |

| Empty protocol | (empty) | TCP | Required field |

Security/Wildcard Errors:

| Issue | Before | After | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overly permissive | * | 10.12.0.1 | Wildcard not allowed |

| Broad CIDR | 0.0.0.0/0 | 10.12.0.0/24 | Avoid internet-wide access |

Priority Conflicts:

- Conflict2: Changed priority

1000→1001(was duplicate with Conflict1)

The amended file looks a bit like this:

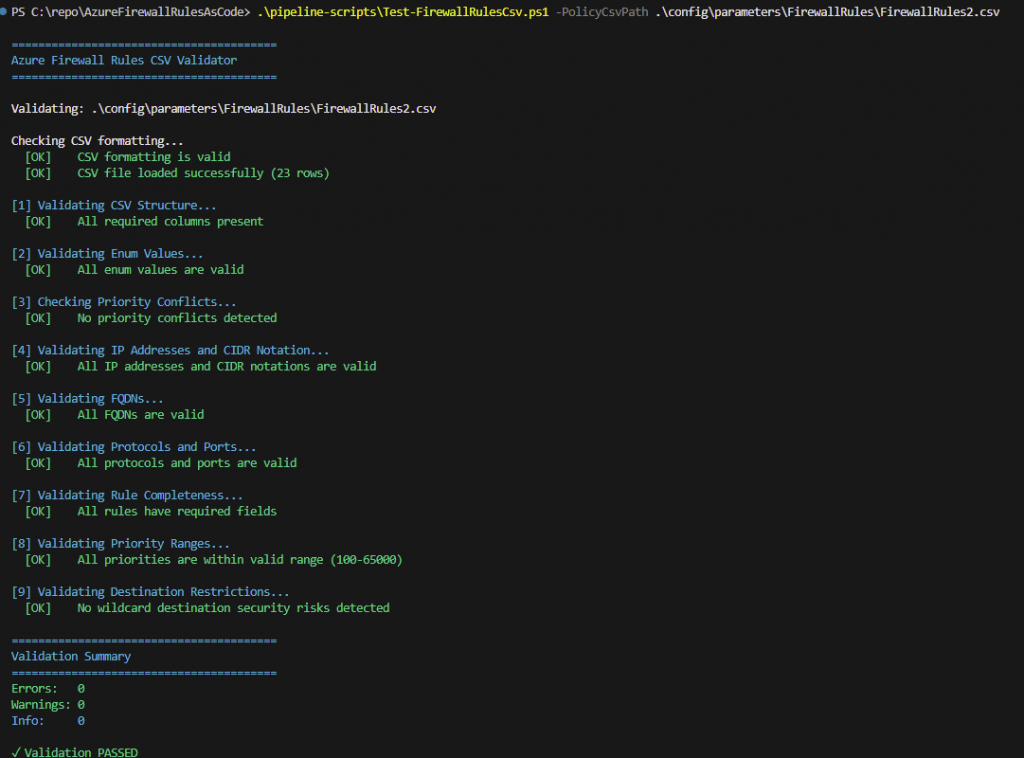

Re-run the validation script and all looks good!

What I found particularly valuable during this testing was how quickly the script surfaced issues. Rather than deploying to Azure, waiting for a failure, then debugging, I could iterate locally and fix 15+ issues in about 10 minutes. This is exactly the ‘fail fast’ principle that makes shift-left effective.

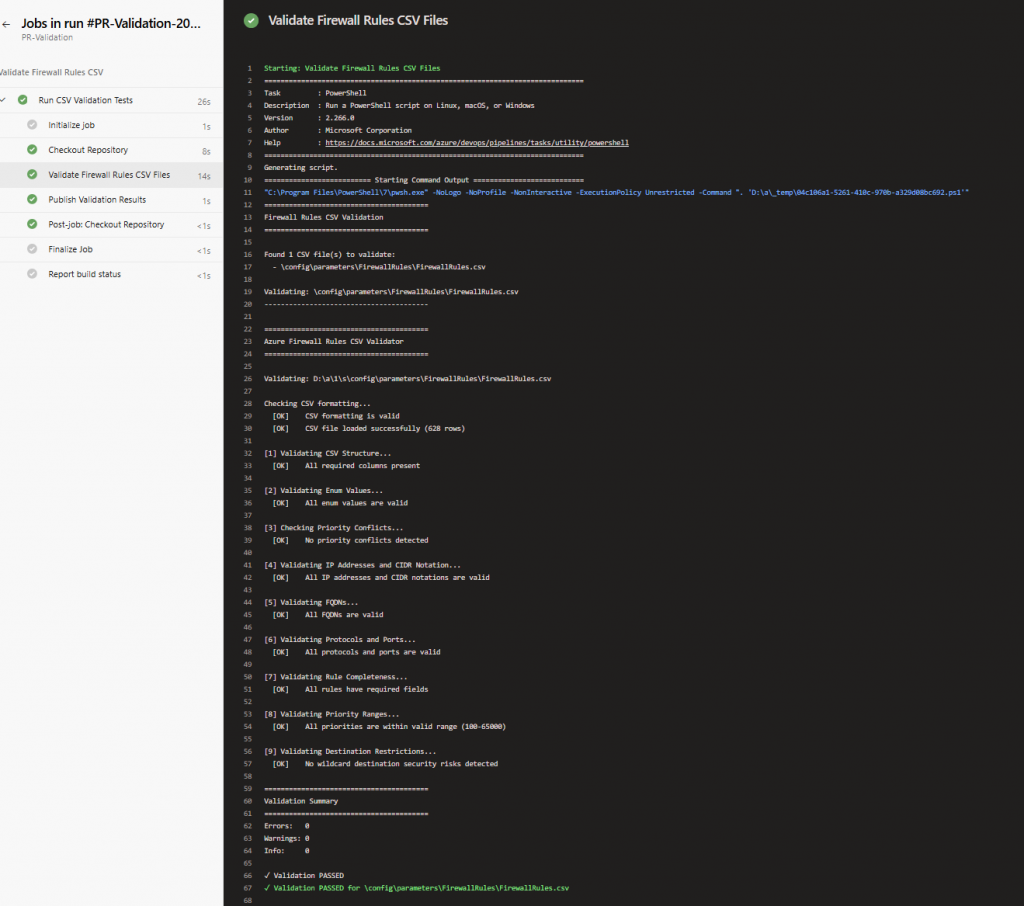

So now it’s time to implement this as part of the automated testing in a DevOps pipeline, in the repo there is a pipeline ready for deployment in Azure DevOps here

With the validation script working locally, the next step was integrating it into the PR workflow we established in post 2. The PR-Validation.yaml pipeline is triggered automatically whenever someone opens a pull request that modifies FirewallRules.csv

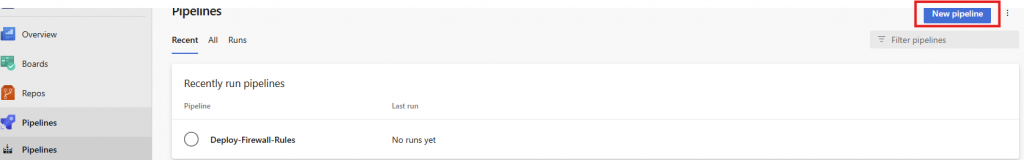

In Azure DevOps create a New pipeline

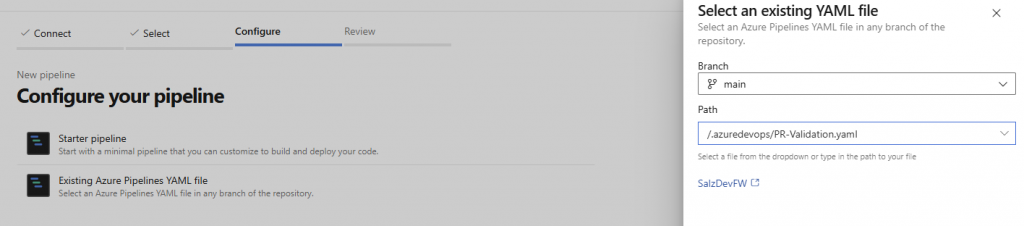

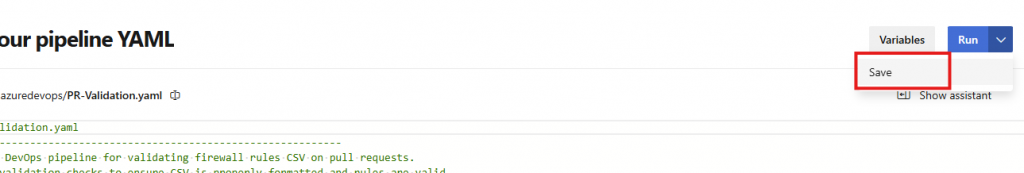

Locate the PR Validation yaml

Then save it

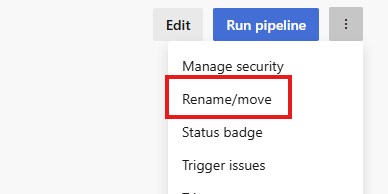

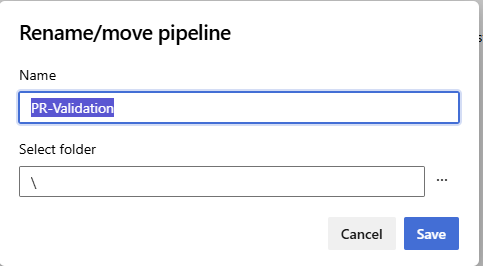

I then generally rename the pipeline to something relevant, in this case PR Validation

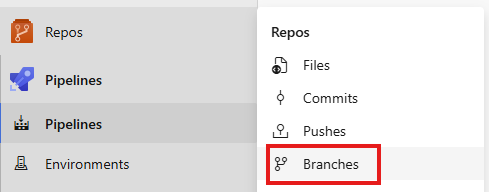

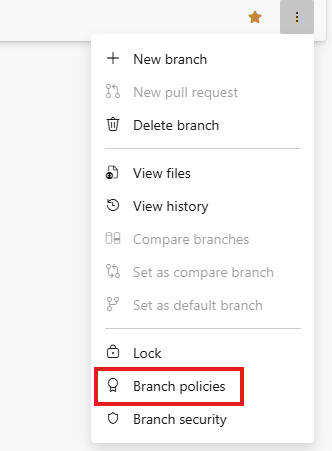

Then we need to set this pipeline as the automated run when a Pull Request is made, select Repos, then branches

Select Branch Policies on main

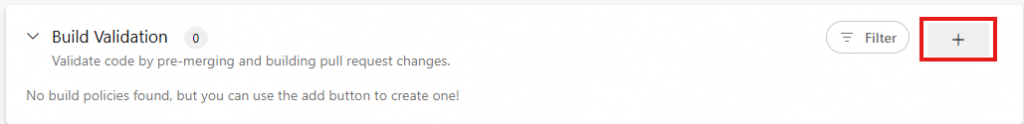

Select the + on build validation

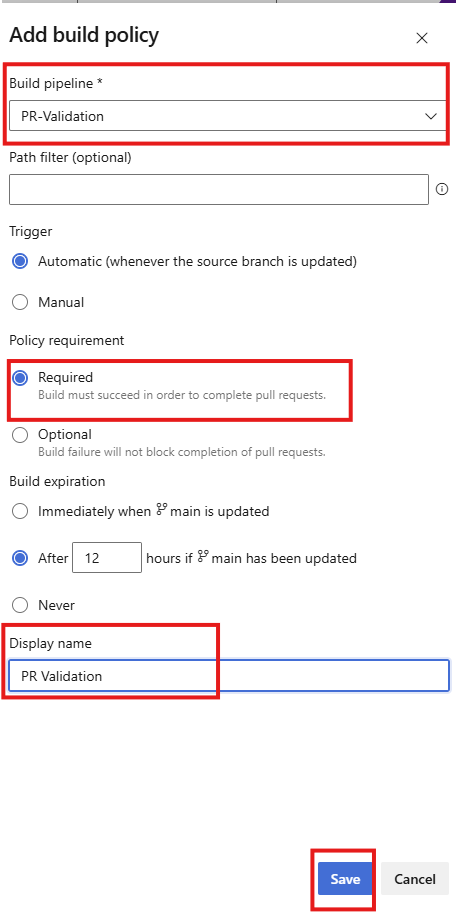

Select the pipeline,, make sure its Automatic and Required, then give it a name and select save

By making this pipeline required, we ensure that no one can merge a PR with invalid rules. This combines with the manual approvals we set up previously — the technical validation must pass before humans even start reviewing.

Here’s what happens when validation fails. I deliberately introduced an invalid CIDR range (10.0.0.0/35) to test the pipeline behaviour. The PR validation pipeline runs automatically, catches the error, and blocks the merge. The developer sees exactly what’s wrong directly in the Azure DevOps interface, no need to dig through deployment logs or wait for Azure to reject the configuration.

Once I fixed the CIDR notation errors, the pipeline ran again automatically and passed. At this point, the PR is ready for human review. The automated tests have already validated the technical correctness, reviewers can focus on whether the rules make sense from a security and business perspective.

With automated validation now integrated into the pipeline, we’ve completed the shift-left journey, moving security checks earlier in the workflow and reducing deployment risk. Future enhancements will expand coverage to IP group validation and deeper rule logic

Leave a Reply